Lesion of the meniscus

An Injury-prone Joint

The human knee joint is the largest and most complicated joint in the human body, as well as one of the most sensitive ones. How well our knee is "designed" is shown by the fact that, despite enormous scientific advance in recent years and despite the most modern materials, so far there has been no success in imitating the entire functionality of the human knee in the laboratory.

To enable us humans to walk upright, the knee joint must simultaneously combine two opposing construction principles in itself: on the one hand, the best possible movement must be guaranteed in bending, while on the other, the knee joint must guarantee maximum stability in stretched out position.

At the same time, the knee joint is the most heavily loaded joint in the human body. Through the lever effect and through acceleration forces of the entire body weight, it can at times, such as in sports, be loaded with forces of up to 2 tons. The knee can cope well with these enormous forces, provided the force works physiologically, meaning that it is distributed evenly over the surface of the knee joint.

In order for the forces to be distributed evenly, the human knee has various stabilization mechanisms, such as the musculature of the leg, the cruciate ligaments, the joint capsule, and the meniscus.

It is important to view the functionality of the knee joint as the interplay of all these mechanisms. In this sense, a 100% functioning of this joint, especially for a top athlete, can be achieved only when all the components work together; it can be only as strong as its weakest link. For example, if the meniscus is damaged, excess load on the other components of the knee joint occurs, a situation that in the long run leads to even greater problems. Let's turn to a part of this chain, the meniscus.

Structure and Function of the Meniscus

In the human anatomy, the disk shaped cartilage in a joint is called a meniscus; in the knee, it is crescent shaped. In contrast to a disk, a meniscus divides the joint cavity only incompletely. In mammals there are two large menisci in the knee joint, as well as many smaller menisci in other joints (such as in the inter-phalangeal joint); these often lead off from the capsule and project into the joint. The name derives from the Greek, meaning "little moon," based on the shape of the meniscus. Birds too have menisci in joints other than the knee joint ("hand" joint, spinal column).

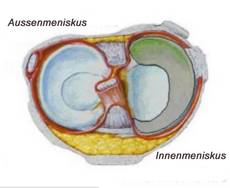

The "meniscus" consists of two crescent shaped elastic disks of fibrous cartilage, the inner and outer meniscus, that are laid out in a circle along the outer contours of the knee joint surface like the flat washers known from mechanics (see illustrations 1-3).

(Illustration 1): The essential structures of the human knee joint. For better illustration, the patella (kneecap) was omitted in this illustration.

(Illustration 2): The "meniscus" consists of two crescent shaped elastic disks of fibrous cartilage, the inner and outer meniscus, that are laid out in a circle along the outer contours of the knee joint surface like the flat washers known from mechanics.

(Illustration 3): In this picture you can see the anatomic structure of both menisci. In the center, the two menisci are divided by the cruciate ligaments. On the left, the outer meniscus (light blue) is next to the cruciate ligament. On the right, the inner meniscus (gray) lies next to the cruciate ligaments. As you can easily see from the illustration, the size of the outer meniscus is much larger than the size of the inner mensicus.

If you slice through a meniscus from top to bottom, a triangular structure is revealed, in which the components found on the outside of the joint are arranged broadly, while toward the middle of the joint they taper into a narrow band of fibrous tissue.

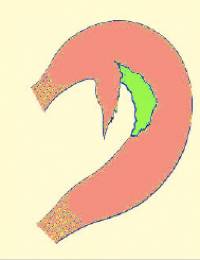

Both menisci are supplied with blood from the joint capsule, that is, from "outside." The supply of blood also determines the division of the menisci into so-called zones. The areas that are well supplied with blood, corresponding to the outer two thirds of the meniscus, are called the red zone. The inner third, which less well supplied with blood or not supplied at all, is called the "white" zone. The significance of the division into zones will become clear in the discussion of meniscus injuries. More of that later.

(Illustration 4): The "meniscus" consists of two crescent shaped, elastic fibrous cartilage disks, the inner and outer meniscus.

The menisci play a weight-bearing role in the distribution of the forces affecting the knee. The task of the meniscus is to guide the movements of the knee joint and to support it, partially to stabilize the joint, and to assure a certain dampening of the shock. On the one hand, the menisci increase the size of the joint surface, with the result that the load is better distributed. On the other hand, by their elasticity, the menisci act as shock absorbers, which "swallow" a portion of the load. Beyond this, the menisci attend to a better distribution of the "joint lubricants."

Another important task for the menisci is the interaction with other stabilization mechanisms of the knee joint, guiding and stabilizing on bending. According to a current theory, the knee joint menisci serve for better distribution of the pressure between the two joint surfaces of the knee (connecting to the femur and the tibia). However, since the human knee menisci contain type 2 collagen fibers, which are chiefly set up for stretch loads, it is possible that the menisci do not only contribute to the distribution of pressure. In such a case, they would have to consist of type 1 fibers. Thus it cannot be excluded that the menisci possibly serve "only" for a better distribution of the joint fluid on the joint cartilage in order to reduce friction and to nourish the cartilage.

Since the risk of a premature arthrosis significantly increases in people who have the meniscus removed operatively, the theory about the even distribution of pressure is today a generally recognized one. Due to the mobility of the menisci (chiefly of the lateral meniscus), the joint surfaces increase on the tibia plateau and on the contact surfaces for the head of the femur. Due to the form of the knee joint (bicondylar joint), in addition to pure bending and stretching movements, rotations by a few degree and shifts (translations) forward and backward are possible. The contact surfaces of the bony tibia plateau would be inadequate for this without the menisci.

Damage to the Meniscus – the Most Common Sports Injury

Menisci can tear because of accidents, strong overloads, or simply because of age-related wear and tear. Those commonly afflicted with meniscus injuries are athletes or people whose work puts excess demands on the knee, such as tile setters. Sports particularly at risk for meniscus injuries include football, skiing, basketball, discus throw, and karate. A meniscus injury usually occurs upon intensive and rapid twisting of the knee joint.

Sudden twisting movements, which exert force diagonally on the knee joint, such as we frequently see in snowboarding accidents, skiing accidents, but also in all running sports, tennis, and football, can lead to meniscus injuries. Such injuries also occur frequently upon twisting and compressing movements, such as in volleyball and basketball.

Natural wear and tear should not be overlooked, for from age 25 onwards the elasticity of the cartilage fiber declines and thus leads to an increased risk of injury.

It is important to know that early joint attrition (knee joint arthrosis) can be furthered by injury to or loss of the meniscus tissue.

Meniscus Lesions

The harmless variant of a meniscus lesion (injury) is called a meniscus compression. An operation with a relieving incision can aid healing in some cases of this type (in German medical language called a Silcher incision).

The case is different with a rupture of the mensicus (meniscus tear). Injuries of the inner meniscus (meniscus medialis) are much more frequent. The tears are categorized by the direction of the tear into radial tears, horseshoe tears (tongue tears), longitudinal tears, bucket handle tears, and surface tears. Diagnosis comes through clinical examination and arthroscopy (imaging of the joint).

A

A

B

B

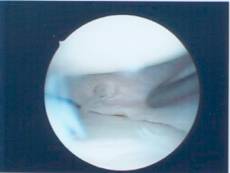

(Illustration 5A (schematic) and 5B (arthroscopic finding): A "meniscus horseshoe tear".

(Illustration 6A (schematic) and 6B (arthroscopic finding): A "meniscus radial tear".

A

A

(Illustration 7A (schematic) and 7B (arthroscopic finding): A "meniscus bucket handle tear".

A bucket handle tear is the name for a meniscus tear running parallel to the main direction of the fibers. In this, the meniscus is split length-wise along its course, while the front and hind ends of the fragment continue to connect to the rest of the meniscus. The free edge is dislocated in the joint area and causes acute pains.

Certain Diagnosis Using Arthroscopy

After an accident, pains in the joint area, swelling of the knee joint, pains on knee extension, or restriction in the ability to bend point to a meniscus lesion. In meniscus tears, the free fluttering pieces often appear in the joint, which can damage the very sensitive joint cartilage, and in the worst cases over longer periods even lead to an arthrosis.

In essence, this principle is applicable:

"A meniscus tear should be repaired as soon as possible in order to prevent subsequent damage."

In an acute case, the meniscus tear is marked by intensive joint pain; the joint is not freely movable at the edges of mobility and may even be blocked. In most cases the pain of a meniscus tear can be localized to the spot of what is called the joint space.

A clinical examination can diagnose a meniscus tear with high probability. Subsequently, an exact description of the meniscus lesion is done using such tools as arthroscopy or magnetic resonance tomography (MRI).

To be absolutely sure of a diagnosis, an arthroscopy – imaging of the knee joint – can be done. While the physician can diagnose the inner area of the joint most exactly, the great advantage of an arthroscopic procedure is that in certain circumstances operative steps can be taken immediately.

In the "keyhole operation" the knee is opened with only a small skin incision. Through this small incision in the knee joint a rod holding a camera is inserted, which transfers pictures of the joint interior to a monitor in the operating room. Another small incision allows the introduction of a palpating hook, which tests the composition of the cartilage, cruciate ligament, and the menisci. It is then possible to introduce other instruments through this second incision so that, for example, free floating pieces of the mensicus can be removed.

The arthroscopic procedure can be done as an out-patient or in-patient (2-3 days) procedure.

In contrast to MRI, arthroscopy is an invasive procedure. In arthroscopy, either under lumbar anesthesia (partial anesthesia in which the patient is awake; only the legs are "asleep" and are insensitive to pain) or full anesthesia, a small camera and instruments are introduced into the knee joint through three small incisions (about 1 cm long).

Using this camera and instruments, the operating physician can obtain an exact picture of the state of the knee joint (e.g., of the joint cartilage, the cruciate ligaments, etc.), can visualize the injury exactly, and above all during the same operation can take appropriate therapeutic measures. Herein lies the great advantage when compared to the non-invasive imaging of the MRI where diagnosis and treatment come in two separate steps.

MRI is preferred for use with fresh injuries, which make clinical examination impossible due to the strong pains, or upon suspected simultaneous injury to the lateral ligaments of the knee joint, in order to get an idea of the extent of the injury.

Treatment Possibilities of a Meniscus Injury

There are essentially two ways to treat torn menisci: Certain tears can be repaired by stitching them together; in other cases the torn piece must be removed, especially when the tear occurs in the meniscus zone that is not fed by blood (white zone). Diagnosis as soon as possible after the injury is essential for the maintenance of the meniscus. If the injury lies in the base meniscus region that is fed by blood (the so-called "red zone" – see above), as in the case of a tear of the base of the meniscus, the blood supply in the injured area of the meniscus is impaired. With every passing day that elapses without action, the chance of healing diminishes.

For a number of years, with the use of modern instruments (e.g., RapidLoc® Mitek Anchor from Johnson & Johnson, see illustration 8), it has been possible to reset a meniscus that has been torn loose from the meniscus base, i.e., the connecting part of the meniscus in the knee joint capsule. This should occur within a few days of the accident; otherwise the fibrous cartilage of the meniscus will be damaged irreparably by the deficient blood circulation. The same applies to a laceration of the meniscus. If this appears in the meniscus region fed with blood, it can be stitched. Here too a good result depends on the time that elapses after the accident.

A

A

B

B

(Illustration 9, schematic image A and arthroscopic finding B): Refixing the torn meniscus – the laceration of the meniscus in the last third (red zone) of the meniscus is clearly visible. The "meniscus" is refixed on its base with a RapidLoc® Mitek anchor from Johnson & Johnson.

In meniscus lesions, longitudinal and radial tears are distinguished. Longitudinal or circumferential tears are those in the direction of the semi-circle of the meniscus. These can be found in either of the two zones. A radial or transverse tear stretches perpendicular to the direction of the fiber, and can affect only one zone or cut through both zones. Naturally, combinations of all tears occur.

As mentioned earlier, damages to the red zone of the menisci are reparable, either through fixation when there is a separating tear from the mensicus base, or through suturing. In this way the meniscus, so important for the functionality of the knee joint, can be maintained.

However, if the lesion lies in the so-called white zone of the meniscus, which is poorly supplied with blood, the injured tissue must be removed in order to prevent progression of the tear, complete detaching, or a painful trapping of the torn piece of tissue in the joint area.

Nonetheless, in very young patients, repair of the tear is attempted. Possibilities exist, for one, with a suture, or with bonding the tear with fibrin (a protein appropriate to the body), or by attempting to stimulate the blood supply with small pin-pricks of the injured region down to the base of the meniscus (what are called vascular channels).

In a "bucket handle lesion" the meniscus is torn in such a way a part can move freely in the joint. This leads to painful trapping, fluid buildup, and sudden stiffness upon movement. As treatment, an attempt is made arthroscopically to refix the freely moving part both in the white and in the red zone.

If a meniscus injury is ignored for too long, reconstructive treatment is no longer possible. The injured part of the meniscus must be removed to relieve the patient's pains and to prevent further damage to the joint.

However, there is a glimmer of hope for patients from whom a large part of the inner, outer, or entire meniscus must be removed.

Synthetic collagen implants or allograft implants (meniscus tissue from human bodies) represent an opportunity to replace the defective meniscus. The implant is sutured to the rest of the meniscus and serves as a building frame for the body's own cartilage cells. Within a year, the implant is completely rebuilt by the body, and in its place a sort of substitute meniscus has developed through the growth of the body's own cells. This method is, to be sure, quite new, but till now it has shown satisfactory results, though without any long-term results yet.

Prevention – Good Blood Circulation is Important

Like any other joint, the knee must be moved so that blood circulates through it. If a person sits for a long time at work, he or she should intermittently get up and move around. To avoid sports injuries, a warm-up is very important. For this, first the large muscle groups should be moved, such as the shoulders, back, and upper legs. Then comes stretching. Every position should be held for at least ten seconds. A maximum period of 15 minutes should lie between the warm-up phase and the actual sports activity.

How Long Will I be Unable to Work?

If the meniscus can be sutured, you should stay at home about one to two weeks, since during this period you will have to use forearm crutches. Patients who perform heavy physical labor must in such cases stay away from work for six to eight weeks. However, if only a partial removal takes place, office workers can return to work without limitation after a week; for physical labor, this period lasts for two to three weeks. Depending on the state of the joint cartilage, one to six weeks may pass before you feel really "normal" in the knee joint.

What Are the Prospects for a Return to Sports?

If the meniscus tear is discovered early, that is, before there is damage to the cartilage surface, you can count on being able to do sports with no limits. Naturally, the recovery period of four to six weeks, as mentioned above, should be observed before renewed sport activity. If cartilage damage already exists, the period before resuming sport activity does not depend on the meniscus injury, but on the healing chances of the cartilage damage. It can happen that certain limitations must be observed for sports on a high level.

P.S. On our website you will find further information regarding treatment for meniscus damage and regarding other treatments by the Orthopedic-trauma-sports medicine department of the Spital Oberengadin:

www.orthopaedie-samedan.ch

www.sportmedizin-samedan.ch